Partners and setting

This study was embedded in a large-scale implementation project to address unmet needs for care for depression in rural communities in three districts of Madhya Pradesh, a central India state with a population of about 72 million. The state is one of the least resourced states in India. The scarcity of trained mental health professionals and their concentration in mental health institutions located in urban areas contribute to a treatment gap of 91% for all mental health problems. [12] In the study districts, mental health services are primarily delivered through Outpatient Department (OPD) consultations provided by district psychiatrists appointed under the District Mental Health Program (DMHP). Besides holding weekly outpatient clinics at the district hospital, the district psychiatrist also visits each Community Health Centre (CHC) once a month. These CHCs, which cater to around 80,000 to 120,000 people, also act as referral hubs for up to four nearby Primary Health Centres (PHCs). There is no mental health service available at the primary health centre (PHC) or at the village level. More recently, a district mental health cell, ‘Mann Kaksh’ [13], has been established. Patients referred to the district hospital and seen at this cell receive free medication and, when required, counselling from a psychologist.

In the post-pandemic context, policy makers have recently recognised the need to supplement mental health care delivery through initiatives such as TeleMANAS (Tele Mental Health Assistance and Networking Across States), which provides free-of-cost mental health services, including psychological counselling and psychiatric consultations, via phone and video calls. It is a significant step to reduce the treatment gap, particularly in underserved rural and remote areas.

This EMPOWER project, implemented by Sangath, a non-governmental organization (NGO) with a long history of mental health implementation science and which had developed the original HAP intervention, was conducted in collaboration with the National Health Mission (NHM) and the Directorate of Health Services of the Government of Madhya Pradesh. Spanning a 2-year period (2021–2023), the project involved engaging with the primary health system in these rural districts, obtaining necessary permissions, establishing referral linkages with ‘Mann Kaksh’ and DMHP, training the ASHAs, screening and delivery of the HAP, independent outcome assessments for a subset of the baseline sample of patients, and public engagement events. This project aims to demonstrate that high-quality mental health services can be embedded within existing health systems using current human resources, requiring minimal investment, and delivered in a non-stigmatizing and acceptable manner to ensure sustainability. We report the evaluation, guided by the RE-AIM framework, of this real-world implementation of the HAP intervention by ASHAs.”

Stakeholder/Gatekeeper engagement

Concurrently to the training of ASHAs, we designed a digital course on ‘Leadership in community mental health’ with the aim of building capacity of health system stakeholders. This course contained lectures from knowledge leaders on community mental health as well as ‘case stories’ about other community mental health projects across the country. This course was intended to secure buy-in and support from the health system for our on-ground activities.

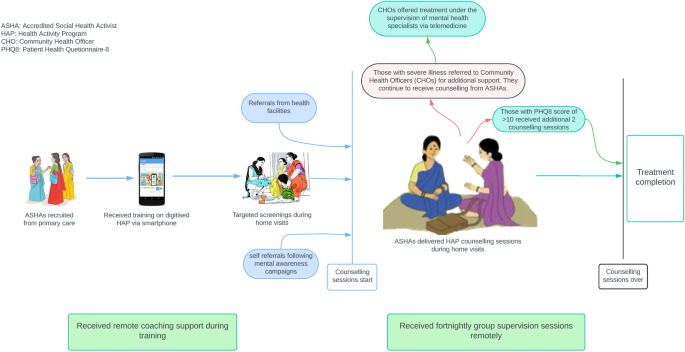

We also recruited volunteers from the community and trained them to conduct screening for depression in the community. These volunteers included village elders, panchayat (village governing council) members, teachers, social workers, and college students. They also participated in and contributed to our public engagement activities to encourage a demand for depression care in the community. We worked with Community Health Officers (CHOs) at Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs), which are a new cadre of non-physician health workers introduced under the Ayushman Bharat initiative [14]. The CHOs play a critical role in delivering an expanded range of essential services and serve as the first point of contact for a population of approximately 5,000 individuals in Madhya Pradesh. We trained this cadre in the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) Mental Health Gap Action Program (mhGAP) intervention guide, which is a set of evidence-based guidelines and tools for non-specialist health workers to assess and manage mental, neurological, and substance use disorders. [15] A total of 213 CHOs were trained across Vidisha, Raisen, and Narmadapuram. This enabled the ASHAs to refer severe or non-responsive patients for specialist support through the CHOs by utilising the telemedicine infrastructure established under the Ayushman Bharat scheme. In collaboration with the District health system, we established referral and support pathways (see Fig. 1). Block Medical Officers (BMOs) supported ASHA training, refreshers, and supervision, motivating ASHAs and participating in training programs. Senior bureaucrats provided guidance, troubleshooting, and progress review, offering insights on navigating challenges like state elections and ASHA strikes. Other grassroots workers, including Auxiliary Nurse Midwives who provide basic healthcare at the village level, and Anganwadi workers who are frontline health workers under the Integrated Child Development Scheme offering health, nutrition, and early education services to children under 6, helped raise mental health awareness during Village Health and Nutrition Days. Local village leaders and panchayat members supported public engagement activities and encouraged families to participate in ASHA-led counselling sessions.

Psychosocial treatment of depression in the community: Referral and support pathways

Providers

ASHAs are India’s most numerous (nearly 1 million) and widely distributed frontline workers. ASHAs, who are all women by design, are incentive based cadres whose original mandate was to promote maternal and child health in rural communities. With the improvements in these health indicators, thanks in large measure due to their deployment, their roles have expanded to addressing issues related to noncommunicable diseases and, most recently, to the door-to-door Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination campaign. Each ASHA caters to about 500 households, is embedded in the community, reports to the BMO and works in close collaboration with the CHO in which her community is located and enjoys trust of and access to people’s homes whom she regularly visits. ASHA routinely visit their assigned households to provide a range of health services, actively engage with the communities and are well versed with the health needs of the households where they serve as a ‘last mile’ health worker. ASHAs are affectionately called ‘Didi’ which means elder sister by the community members.

We recruited ASHAs through purposive sampling (based on their availability, access to a smartphone and digital literacy). They were required to use their phones to complete a fully digitized course to learn the HAP. This digitised course had previously been tested [16] in a nearby district; two trials observed that the effects of digitised training with coaching support on provider competencies was non-inferior to the gold standard of expert-led in-person training. [16, 17] We conducted a 4-h orientation session in local health facilities in which the project team guided the ASHAs to download the Learning Management System (LMS) and navigate its features. Subsequently, ASHAs were required to follow the digital curriculum to learn the HAP. The project team monitored their progress and offered remote coaching for troubleshooting and address queries. As the learner progressed through each module, she undertook an end-of-module assessment. On completion of all the modules, a ‘course completion certificate’ was triggered by the LMS. Following the digital training, ASHAs were required to complete an internship phase involving delivering treatment under supervision by HAP trained counsellors of Sangath team to a minimum of two patients.

We provided the ASHAs with a casebook, which contained prompts on session content to be delivered during each visit as part of the structured HAP counselling package. As they delivered counselling sessions, they received fortnightly group supervision sessions and refresher trainings in which they participated in role plays to further reinforce their counselling skills. The supervision sessions were conducted remotely via zoom calls, with each supervision session bringing together 6–8 ASHAs. Supervision sessions were facilitated by trained HAP supervisors who had either a postgraduate qualification in psychology or in social work. During every supervision session, one of the ASHAs presented a session of one of her patients and all group members then discussed the case and gave feedback. As some of the ASHAs gained experience and skills, they were invited to lead the supervision sessions in line with the evidence-based peer supervision strategy for scale-up and sustainability. [18, 19] ASHAs received incentives for undertaking training, conducting counselling sessions and attending supervision sessions as per the local health system rates.

Patient recruitment

We administered the Hindi version of Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8) [20] to identify patients; while the full version of the PHQ has nine items, the ninth item, referring to suicidal ideation, was removed systematically because local experience demonstrated that this item was rarely endorsed and led to discomfort for both the ASHA and the respondent. Even so, the PHQ-8 is a widely used measure for assessing symptoms of depression and has good sensitivity and specificity; [21] further, the 8-item version has been validated among Hindi-speaking populations [22]. ASHAs received training on suicide risk management as part of the HAP digital training, reinforced during refresher sessions and supervision. According to Sangath’s standard operating procedure (SOP), if an ASHA became aware of suicidal ideation, the patient would be assessed by a HAP supervisor or psychologist and referred to district mental health services.

ASHAs were encouraged to screen adults during their routine household visits. Individuals scoring 10 or above were considered to have clinically significant depressive symptoms and were offered the 6-session HAP. After completion of the treatment, the PHQ-8 was reassessed, and those still scoring 10 or above were provided with 2 additional counselling sessions. If high scores persisted after the 8th session, referral to a CHO was initiated, with treatment overseen by a mental health specialist (Fig. 1). The patient being referred to the CHO for consultation is accompanied by the ASHA, who can access mental health specialist through the health department’s telemedicine portal. She continues to provide counselling to them and either accompanied or facilitated the appointment at the district health facility if referred further.

Patient and public Involvement

Patients played a crucial role in the planning and implementation of our project, significantly influencing the delivery of psychological treatment. Patients’ feedback on issues related to.

(a) Stigmatization i.e. apprehension about receiving mental health-related services in public health facilities and (b) accessibility issues of the health facilities being located at considerable distances, posing challenges, particularly for women, prompted to adopt a visit-at-home strategy for treatment delivery. At times, patients suggested alternative locations such as nearby temples, schools, or panchayats, due to discomfort in discussing their confidential issues in presence of other family members.

Community members actively participated in dissemination events designed to raise mental health awareness. These events included street plays and a reel-making competition, both of which were well-received and effectively engaged the community in mental health discourse.

Data collection

We collected a range of data:

ASHA training and supervision session attendance

We generated back-end data from the LMS to estimate the number of days taken to complete the online training. Attendance logs for supervision were maintained by the project team for all the ASHAs who were delivering sessions.

Patient treatment engagement and outcome scores: We collected process data on screening numbers, patient recruitment, baseline and end-of-treatment PHQ-8 scores, counselling session counts, duration of treatment. Nine-month PHQ-8 scores were collected through independent assessors by deploying consecutive sampling to achieve a follow-up sample subsample size of 10% of the baseline sample original cohort from within the original cohort. Outcome data could not be collected for treatment dropouts (n = 48, 2.17%).

Satisfaction questionnaires

We administered satisfaction questionnaires to a subsample of ASHAs and patients. The ASHA questionnaire comprising 6 items rated on a five-point Likert scale was administered to a subset of the providers (n = 256). The patient questionnaire comprising 5 items was administered to a subset of the patients (n = 755). The ASHA Satisfaction Questionnaire and Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire were developed specifically for this study and can be accessed as Supplementary Material 1 and Supplementary Material 2, respectively.

Analyses

All analyses were conducted on STATA version 17. We ran a descriptive analysis on the socio-demographic, i.e., ASHA (education, age, marital status) and patient (age) data. Descriptive analysis was also deployed to analyse the project implementation data of ASHA performance metrics (days taken to complete HAP course, number of patients seen) and therapy metrics (Baseline PHQ-8, Post treatment PHQ-8, Independent PHQ-8, treatment duration).

Responses to ASHA and patient satisfaction questionnaires were analysed descriptively. A two-level mixed-effect regression model was employed to examine the relationship between various factors—including baseline PHQ-8 score, patient age, gender, treatment duration, ASHA age, ASHA education, supervision sessions attended by the ASHA—and the end-of-treatment PHQ-8 score. This model addressed the clustering of data by ASHAs, capturing both correlated effects and variations between different providers. The Wald chi-square test detected a significant effect (χ2 = 30.43, p < 0.001), highlighting the importance of addressing variability at the group level. Our model, which achieved a log likelihood of −3811.788, demonstrated superior fit compared to alternative approaches.

link